News & Updates

The First Planting Contract: Up The Wildhorse in 1970

9

By Dirk Brinkman

August 1970, fighting fire as a faller north of Golden, I strapped the slashing contractor whose crew started the fire onto the helicopter skid after a fallen tree cracked his cervical vertebrae-- wiring his hardhat to the stretcher basket as a windfairing to protect him on the long flight to Nelson over the Purcell Mountains. Nearly bankrupt for having to fight the fire with his whole crew on his payroll, he was worrying about the bill for all of the timber burnt when he had his accident. Later that week i took a fall climbing. At that moment I truly met Ted Davis, whose climbing caution i had initially misread as timidness, and suddenly realized was expertize.

When Red Wassick, the Kootenay Forest Service Region’s Fire legend, called us out to a stump speech, delivered in his usual brusque style--shifting a toothpick from one side of his mouth to the other between bellowed phrases: “This fire’s going out!” “You’ll get your cheques tonight!” “We’ll be checking your trucks for our Forest Service gear on your way out!” and “Cranbrook District Office is letting some planting contracts!”

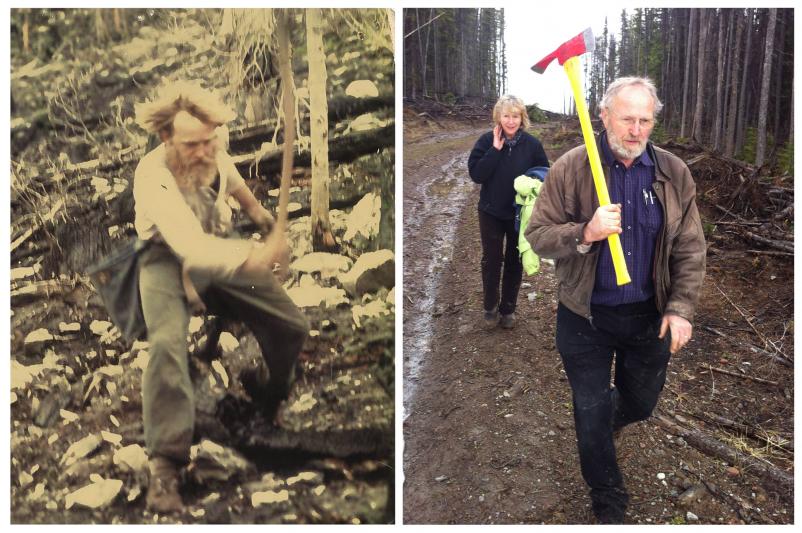

Ted the draft dodger who had planted in Oregon and Dirk the BC slashing contractor both needed more work-- a good combination, planter and contractor, cautious adventurer and risk taker. Sixteen year old Dan Oppewal, son of one of my College professors, made a crew of three.

We bid lowest on the remotest contract and were required to sign an affidavit we would hire 12 planters from the District office lists if we did not average over 1000 trees per day in the first week. We started Sept 08 and they wanted our 100,000 trees in the 6500’ ground before the snow flew in early October. The district’s record number of trees planted in one day was 600. To finish we needed to average 1333 trees per day over the next three weeks, we averaged over 1400—BC’s first highball crew put 96,000 trees in the ground by Sept 30.

Every morning the checker would step out of his truck and exclaim with a big smile “Socked right in in the valley! Clear as a bell in the mountains!” Camped at the base of the block on Wildhorse Creek under a plastic covered pole frame we were typically bagging up our second run as he arrived.

Nice guy or not, BC’s first contractors and contract planting checkers had some conflict. The first morning, after issuing the bareroot spruce seedlings, Forest Service hoedads and canvas seedling buckets, he pointed to a lone tree at the back edge of the block and said ‘plant that straight line and if you work alongside each other you get perfect spacing. Then he loaded some bareroot seedlings in the canvas rope handled bucket, set his seedling bucket down carefully alongside the first planting spot and excavated a large opening. Setting his hoedad down he selected a seedling from the bag and inserted it in the hole using his hands and then the hoedad to backfill the hole, and tamp the seedling to make it vertical. Then picking up the bucket he marched 8’ exactly to the next spot along his compass line, smiling as he explained each action.

While we listened respectfully, we did not imitate him. Sitting down and pulling out our knives, we unknotted the woven rope handles from the metal eyes in the canvas seedling buckets. Unsmiling he pulled out his triplicate notebook with its yellow and pink carbon forms, and ‘wrote us up’ “Damaging government property”. After getting my signature happily acknowledging what we had done, he explained as he handed us our pink copy that after three of these, there would be a fine.

Next we punched holes in the canvas just under the rope sown into the canvas bucket rim--another pink slip. We used haywire to ‘sow’ the buckets into fireman belts from Cranbrooks’ Army Surplus. I wired one bucket to each side of my belt and Ted wired both bags to his left side so he did not have to stop to switch trees to the other bag. Then we set out, slamming the hoedad into the ground and tucking the seedling roots into the hole as we moved on, tamping the seedling as we rose to swing again.

A pink slip for poor planting technique, then a pink slip for not planting a straight line. After exclaiming we hated trees in rows and loved the random spacing of nature, we explained we were following the contour of the block edge and the next planter simply followed that wandering line, working around rocks and logs without interrupting planting.

In all these matters my previous slashing contract experience stood us in good stead. For each issue I simply asked the checker to show me where in the contract it prescribed what he was requiring. Most days he came back with his boss, or his boss’s boss etc. One day, his manager and he were sure they ‘had’ us – the numbers of trees in his plots varied from six to eleven while the contract required 8 trees in each plot (680/acre).

Faced with the threat of being shut down for poor spacing, we set out sixteen rocks on the main landing in a pattern everyone agreed was perfect spacing. Then we challenged him to vary his plot centres and give us some plots. A plot centre right by a tree got 12 and a plot centre in the tree squares middle got 6. In minutes, he recorded all the numbers he was getting on the block. When we asked “How do you taking into account slash, rock and residuals?” he drove down to call the Kootenay District forest mensurationist.

By this point his and my records were into his second triplicate notebook. We kept the smiling checker distraction to a minimum, responding politely but firmly, keeping our focus on getting the trees in the ground before the snow flies. We required he find us on the block where we were planting, as we did not have time to stop, and it was better to comment on what was happening and as we were learning silviculture on the job.

Our contract proceeds distribution plan was part of what drove us. We agreed to each earn the number of trees we each planted, less costs. So we competed with ourselves and each other, crew planting and recording each day’s totals and box count reconciliations together. Costs were kept down by canned food bought from Safeway and cases of discarded vegetables scavenged from behind Safeway. Costs of .3 cents from the 5.3 cent bid left 5 cents a tree.

One day, about two weeks into the project, the Cranbrook District office took more severe measures, Ted, Dan and I were planting up the hill at the far back of the block when we saw smoke billowing from the small grove of trees alongside the creek. Had we left our airtight stove going? Whatever! Our camp was on fire!

I will never forget coming around the bend full-out, all my ribs absolutely aching from the run, to see Red Wassick shifting a tooth pick back and forth across the big grin on his face, as he stood beside the burning pile of our empty boxes. Having experienced firsthand the contractors’ consequence of an escaped fire, we had not dared burn that huge pile nor expected anyone else would.

With Red were Dave Wallinger and Pete Robson, heads of the BC’s provincial reforestation program who had flown to Cranbrook from Victoria and driven up with our smiling checker. Instead, as we had always done to our checker, of getting him to find us, Red had gotten us to come to him.

Dave Wallinger still has kind words for how positively he and Pete viewed how we did what we were doing. It was everything they had hoped for from their contract tree planting idea. We averaged 1400 trees per day (3X average provincial production at the time) on a difficult project. This increased efficiency over the local hourly wage crews meant they could expand the program.

Red Wassick’s red carpet treatment after so many pink slips was anti-climactic. Instead of a reprimand, we were slapped on the back for standing our ground and going ahead with great job. That contract’s unique aha moment recognized the both steep learning curves -- our well intentioned checkers’ and ours.

In transforming the art of reforestation into a remote wilderness adventure of experimenting with alternative work games and life styles, we also solved a difficult ‘public good’ problem-- how to reforest harvested areas more economically.

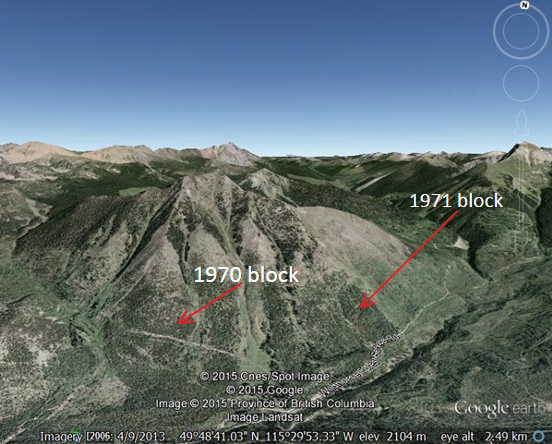

At that time, the objective of reforestation was to reduce the “regen delay” – that is, to reduce the time gap between harvesting and natural regeneration. In 1970, the province estimated the average regen delay was 21 years. But these Wildhorse Creek planted blocks still stand out against the treeless areas around our block today. When you Google this project we can see that in the high altitudes of the Rockies, the ‘regen delay can be 45-years.

Taken as a provincial average, the graph below show BC’s regen delay gradually declining from that first contract year1970, to the year 2000 when the regen delay began to level off from the prompt planting of harvested areas with natural regen problems.

Today’s best planting practices evolved rapidly through the low-bid contracts of the seventies. Inefficient contractors were eliminated by the low bid system, and the fittest, fastest, best quality and most organized planting operations survived. The Canadian sub-culture of tree planting borrowed from parallel extreme sports for equipment and the pursuit of ‘flow’, evolving into what may be the worlds’ most extreme work/sport. In 1975, Ted stepped back to make way for Joyce Murray, who co-lead the business evolution in that highly competitive climate which drove continuous quality improvement, innovation and evolved new organizational systems and techniques.

In 1987, the Cranbrook District office gave us their Wildhorse Award and here we are in 2015 still planting harvest areas around Cranbrook including for BCTS out of the District Office.

Not much has changed. Though planter production has doubled, planter earnings just kept up with inflation. Though safety and camp life is more comfortable --new camps, outdoor clothing, camping gear, footwear, new planting tools--the authentic adventure of the planting experience has not been lost. Planting is still a wilderness adventure in alternative work games and life style experimentation. Both those in the field and those overseeing experience the treeplanting challenge as a challenge of self-development and self-transformation.

Our struggle with our personal limitations and the limits of cooperation is the struggle of our civilizations’ forest stewards. Intelligent stewards can lose themselves in the flow of tree planting, for therein lies the renewal of life for us all.

Hacienda Doña Victoria, Palmar Sur, Puntarenas, Costa Rica

Hacienda Doña Victoria, Palmar Sur, Puntarenas, Costa Rica (506) 8847-0521

(506) 8847-0521